I share monthly-ish stories about culture and diasporas, and I’d love to write to you.

Dear friends,

I write this from my family home exactly a month after George Floyd’s murder. The last few weeks have been a strange mix of violence and comfort, where I’ve felt both annihilated by the news and nestled in the people and spaces dearest to me. It has all made me think about the violence in comfort—to question the racist ideas I’ve imbibed and sustained from the warmth of my own home.

This maildrop is about my lived experience of beauty. Our judgements of beauty are one of the subtlest and sharpest ways that we perpetuate racism. I have always known that beauty means desirability, inclusion, and power. For a long time, however, I also assumed that beauty meant looking or living like a white celebrity or athlete.

If this resonates or you have any thoughts, I would love to hear from you.

Love,

Mishti

I credit my love of mushrooms to Aishwarya Rai. We were at a Jersey pizza joint, I was five, and the black fungi that I’d never before eaten slimed up my plate. Aishwarya Rai eats mushrooms, an uncle told me in a creative flash.

Aishwarya Rai had blue eyes, fair skin, long hair, and a perfect nose. Aishwarya Rai was deemed the most beautiful woman in the world by David Letterman, an American man. And Aishwarya Rai ate mushrooms, so I did too.

My hair grew longer, but my eyes and skin stayed brown and turned even darker each summer, no matter how much sunscreen I lathered on. On the first day of fifth grade, a pink-nosed classmate exclaimed about how tan I was. “But look,” I said, pressing the pale stripe of skin under my wristwatch against her arm. My un-tanned skin was the same color swatch as her tanned skin. This isn’t the original me, I was saying without words, enshrining already that white was better than brown, and brown was better than black.

Every day as a kid, I scrutinized my body in the mirror. I wished for skinnier legs, less body hair, and a straighter nose. I wondered what I’d look like if I were taller or had less myopic vision. I daydreamed about having the gray, green, or hazel eyes of my parents’ cousins, discovering a company a few towns away that allegedly singed off iris pigment to lighten eyes. Ibram X. Kendi recounts a similar desire in How to be an Antiracist, asking “Why did I think lighter eyes were more attractive on me? What did I truly want?”

“I wanted to be Black,” he writes, “but I didn’t want to look Black.” I wanted to be Indian—but I wanted to look beautiful.

My favorite childhood protagonists were tomboyish, bookish white girls like Hermione Granger, Jo March, Nancy Drew, or the heroines of Tamora Pierce. I liked them because they defied feminine stereotypes—they were strong, smart, and adventurous. Similarly, I liked irreverent and cross-cultural movie stars like Jess in Bend it Like Beckham or Aishwarya in Bride & Prejudice, who often landed the cute white guy instead of the Indian suitor their parents wanted.

I grew into some version of them all, reading madly, refusing to cook on principle, quitting dance for the drums, and crushing mostly on white guys while never expecting reciprocation. I hung out with a solid guy gang, the few other Indian kids in my majority-Italian town. They were my best friends—we dealt Pokémon cards at Catholic school mass, ran playground races, sparred in foosball matches, and went to each others’ birthdays—but I never “liked” them. It would’ve felt too stereotypical. Instead, I liked cool moppy-haired jocks with names like Nick or Dylan. These crushes were always a one-way street, but I didn’t mind.

Registering as fact that I wasn’t cute, I instead earned social status through things I could control, like school or sports. In sixth grade, I beat Nick for class president; by high school, I had captained varsity tennis, won awards for my art, scored Ivy League acceptances, and collected a wonderful web of friends. I was happy, but still never thought I was pretty— at least not by the standards of the average teen boy. The first time a boy tried to kiss me, I was so shocked that I recoiled and had to ask him to try again. After we started dating, I noticed stares when we walked in NYC, one man even asking if he could photograph our hands together, white on brown.

By the time I broke up with my boyfriend four years later, my self-image and desires had shifted, albeit partially. I finally thought I was beautiful enough, though I was still surprised when others expressed interest in me. I never thought much about my skin or eyes, but getting my first sunburn still felt weirdly like an accomplishment. I described my “type” as bookish, creative, and outdoorsy—perhaps the antithesis of the investment banker WASP—but my Tinder still told a tale of race and class. My super-likes came from brown or black workers in the area, while my matches were a rolodex of white Princetonians.

At the same time, my substrate was changing. In the cosmopolitan watering holes of New York City, San Francisco, and London, “just” being white began to seem boring. People celebrated stars like Beyoncé, fuller-bodied models, and children’s films heroines like Moana or Princess Tiana. Yoga and mindfulness went solidly mainstream (maybe too mainstream, I thought, when a boy at college shabbat told me he had a Buddhist fetish). Things that had felt awkward in elementary school—brownness, Bollywood, Hinduism—were now interesting and even attractive. With my increased self-confidence combined with this social shift towards multiculturalism, it was easier than ever to ignore the racist beauty standards that continued to thrive.

Ethnic ambiguity is in, but on a foundation of lightness. Today, my younger sister’s Instagram feed is one long scroll of the face Jia Tolentino calls “ambiguously ethnic, but distinctly white,” like “a National Geographic composite illustrating what Americans will look like in 2050, if every American of the future were to be a direct descendant of Kim Kardashian West, Bella Hadid, Emily Ratajkowski, and Kendall Jenner (who looks exactly like Emily Ratajkowski).”

“It’s cool to be ethnic,” as an anthropology grad student told to me at a winter party, “but only in the right ways.”

“Ethnic” spans a broad and messy spectrum between white and black. I’ve passed as Mediterranean in Athens, Cuban in Havana, and Israeli in the tourist havens of ex-IDF soldiers in India. Each time someone has pegged me as a certain race, I’ve known whether I’ve gained or lost power in their eyes.

Lightness has almost always been a beauty upgrade, even within communities of color. In Ghana, my driver told me men loved “light-skinned women like me”; in China, people asked for selfies and let me cut lines when I was with white friends. After centuries of colonization, in India, people still idealize fair skin. Bombay hosts apartment buildings full of Eastern European women who find jobs as Bollywood backup dancers and retail models. German tourists probe Himalayan villages for “pure Aryan” sperm, while concerned mothers warn their girls to avoid the sun unless they want to end up kallu (black). Media magnates and parents, perhaps unwittingly, power a vicious chicken-and-egg cycle of wannabe whiteness.

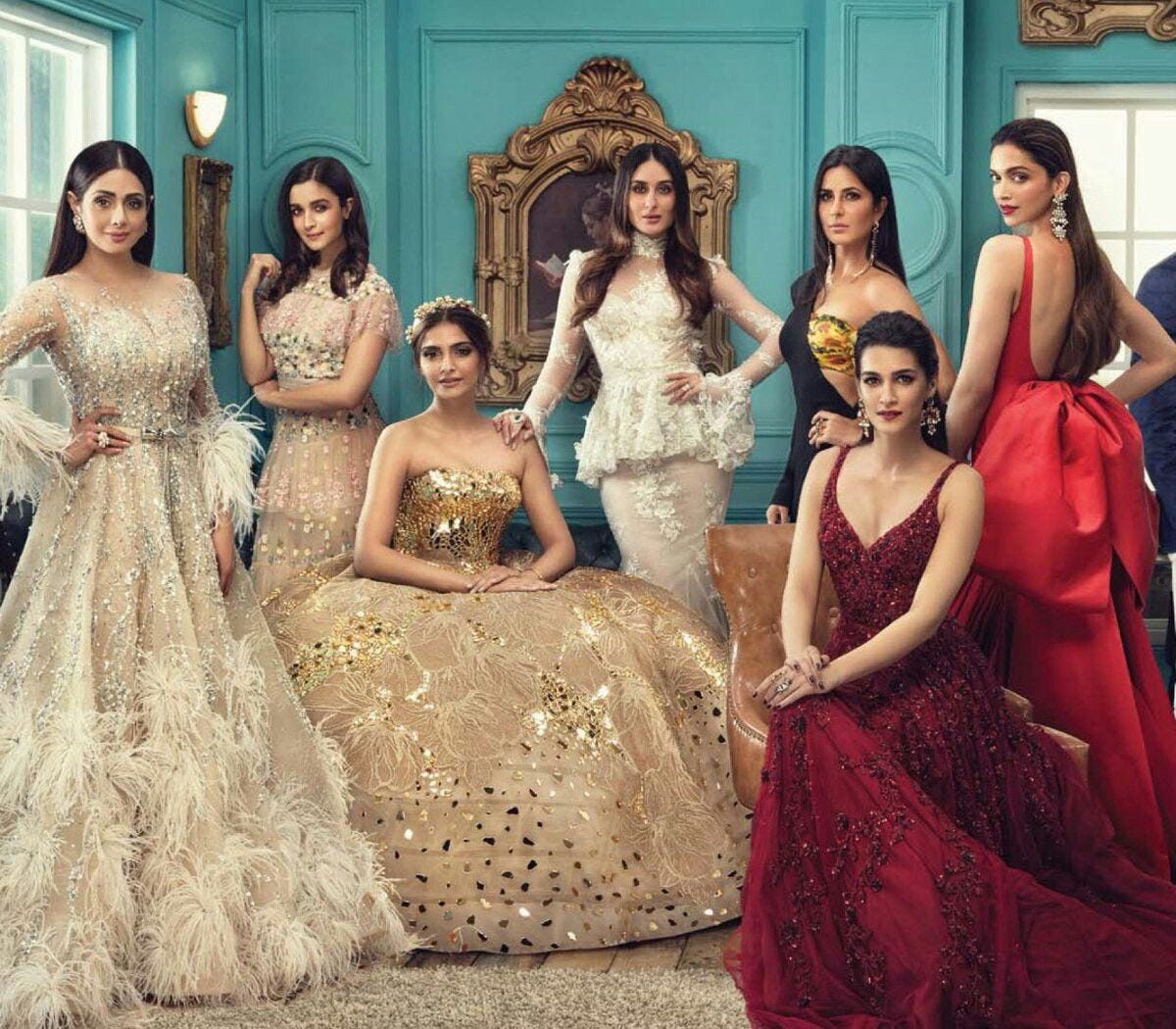

Bollywood actresses in a Filmfare magazine shoot, 2018.I, too, have casually associated with and upheld whiteness. Before I moved to India, yet another friend warned me that my campus dating and gender norms would be way different than I was used to. “I know,” I replied reflexively, “I don’t know where I’ll find other white people.” We stared at each other and burst out laughing in some strange mixture of shame and hilarity. More recently, a Belgian hiker asked me at a mountain hotspring if I was really full Indian. “I would have sworn not more than half!” I blushed like it was a compliment, and then again because I was embarrassed for thinking so. If I looked “full Indian,” would we have been talking?

At the same time, I’ve dropped the lightness to blend in when it suits me. I’ve kept a low profile and bargained for fair prices in India’s street markets and taxi stands. And when I’ve wanted to hear someone’s real story—whether a Harlem security guard or a Paterson shopowner—it’s been best to be an Indian immigrant. Associating with brownness, however, hasn’t always felt more “authentic.” When I was writing college and fellowship essays, I was always advised to lean into being a woman of color. After years climbing a social ladder built on whiteness, I was content being the only brown girl on hiking trips, venture capital meetings, or philosophy graduate seminars. Emphasizing my identity as a woman of color seemed like an opportunistic lie, cashing in benefits to alienation I felt I’d never faced.

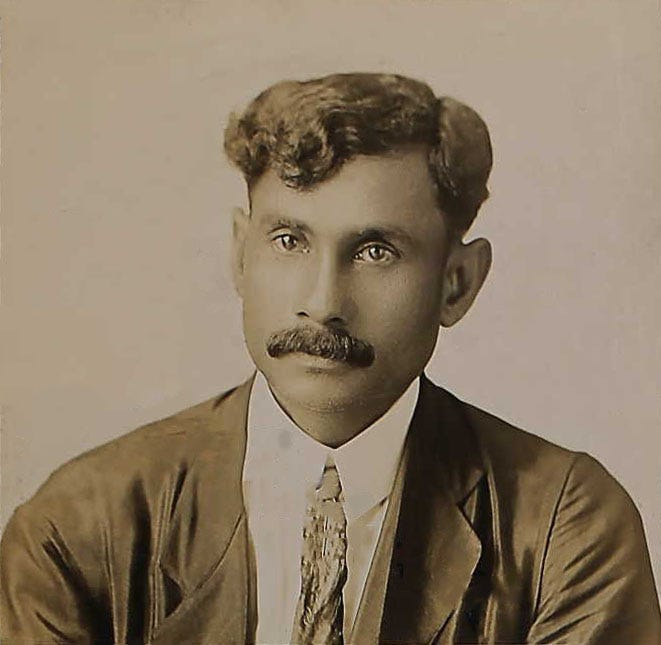

These power games of beauty and race have existed for decades. Vivek Bald’s Bengali Harlem describes Black Americans in the early 1900s who donned turbans to pass as Indian, and Indian traders who in turn applied for citizenship as whites. A Savannah judge granted one Calcutta trader’s claim after rolling up his sleeve for a skin examination, satisfied that “while his face and hands had been darkened by the sun, his unexposed skin was several shares lighter...and sufficiently transparent for the blue color of his veins to show.” As my fifth-grade watch tan shows, things change more slowly than we might think.

Every time I’ve wished for whiteness, I’ve implied that blackness is undesirable. I’ve “passed” as lighter or darker to accommodate my needs, but failed to stand against the rules of game in the first place. Each action has contributed to violence and real consequences for black and brown kids who feel undesirable and alone, growing into adults who are denied the attention, power, and space to live full lives—or to live, at all.

Noorul Huck Akunjee, a Bengali trader who applied for U.S. citizenship in the early 1900s and was categorized as white on his WW1 draft registration (from Louis Takacs).“To be an antiracist is to diversify our standards of beauty like our standards of culture or intelligence, to see beauty equally in all skin colors, broad and thin noses, kinky and straight hair, light and dark eyes. To be an antiracist is to build and live in a beauty culture that accentuates instead of erases our natural beauty.” —Ibram X. Kendi, How to be an Antiracist

Our insecurities about our bodies remain often unsaid, but never private: they cascade into the lives of everyone we touch. In a world that equally celebrated the beauty of different kinds of bodies, personalities, and cultures, how many people would still be breathing?

Kendi’s antiracist standard is a directive to expand our concepts of beauty, to be self-assured about our own appearance without degrading people with different physical traits. It is a mission that applies to anyone who has ever woken up in the morning and taken a critical look in the mirror.

My reflections on beauty continue to be a messy mix of self-worth and internalized value judgements about body type, personality, or race. I still scrutinize my body every day, but I think hard about the imprints that my judgements leave on others. Slowly, I hope, my gaze grows kinder.

Exactly a year ago under the midnight sun in Lofoten, Norway.

Share this post