I share monthly-ish stories about people and places across India and the US, and I’d love to write to you.

Dear friends,

Language is a magic that both empowers and exposes. Through our speech, we touch others but also, inescapably, bare who we are—how old, healthy, happy, or familiar.

As children, we delight in language, fearlessly botching Arabic emphatics or Norwegian retroflexes until they click exactly right. Slowly, though, we start to hesitate, realizing how our speech can brand us as insiders or outsiders. We cling to the tongues we know and stop trying to pronounce what is unfamiliar. The consequences of that fear run deep, flattening generations of Siddharthas into Sids and Josés into Joes.

In this maildrop, I explore the languages, accents, and names I’ve worn over time. For fun, I also recorded myself reading this (with authentic content from Karol G and my cabdrivers interspersed!) Please write back, especially if this resonates with your own experiences, and feel free to forward along.

Love,

Mishti

I am my parents’ first child, born when they were five years older than I am now. My name was a big decision—it needed to have weight and meaning, to be a bright light for the future. The options were endless, since no Indian doctor could legally reveal my gender, though Papa sang achchi achchi gudiya de do na to my mother’s growing belly until they had willed a girl into the world.

When I arrived, my parents still hadn’t found the right fit, so they just scrawled “Baby Anju” onto my birth certificate, nicknamed me Mishti, and kept thinking. It took them a year to land upon Vidushi, wise one, from the Sanskrit vid for knowledge. They can’t remember where they found the name—perhaps in someone’s offhand commentary at the bank or a crinkled paperback from the Lucknow book market—but they know that there had been no debate about it. It just fit.

Nearly a decade later, alone in our computer room, I made a fake Yahoo Answers account under the alias Eva and asked the Baby Names section for opinions on Vidushi. The users were unanimously horrified. “Please do not do that to your kid,” they said. I Googled the word douche for the first time and my stomach sank. I deleted my account without trying to explain that the d in my name sounds like the (tongue against back of front teeth), not do (tongue against roof of mouth). Those millimeters of space felt impossible to bridge.

I never considered anglicizing my name, though this would have had plenty of precedent, from Nikki (Namrata) Haley to Mindy Kaling (Chokingalam). Mamma once asked me if I ever wanted to legally change my name to Mishti, guiding me through the registration for my first AOL account. Mishti, which just means sweet in Bengali, is easy enough to pronounce.

“How cute!” the people on Yahoo answers said. “Unique!”

I looked up at her, our index fingers paused over on the mouse, and I knew I would never do it. My name was important; Vidushi I remained.

I’ve flip-flopped between both two names and two languages for most of my life. When we moved to America, I didn’t speak a word of English. I showed up to pre-k with a coconut oiled bowl cut and Hindi translations taped to my backpack in my mom’s loopy handwriting, doodh for milk and ghar for home. I learned fast, though. Soon, when my parents spoke to me in Hindi, I started to reply in English.

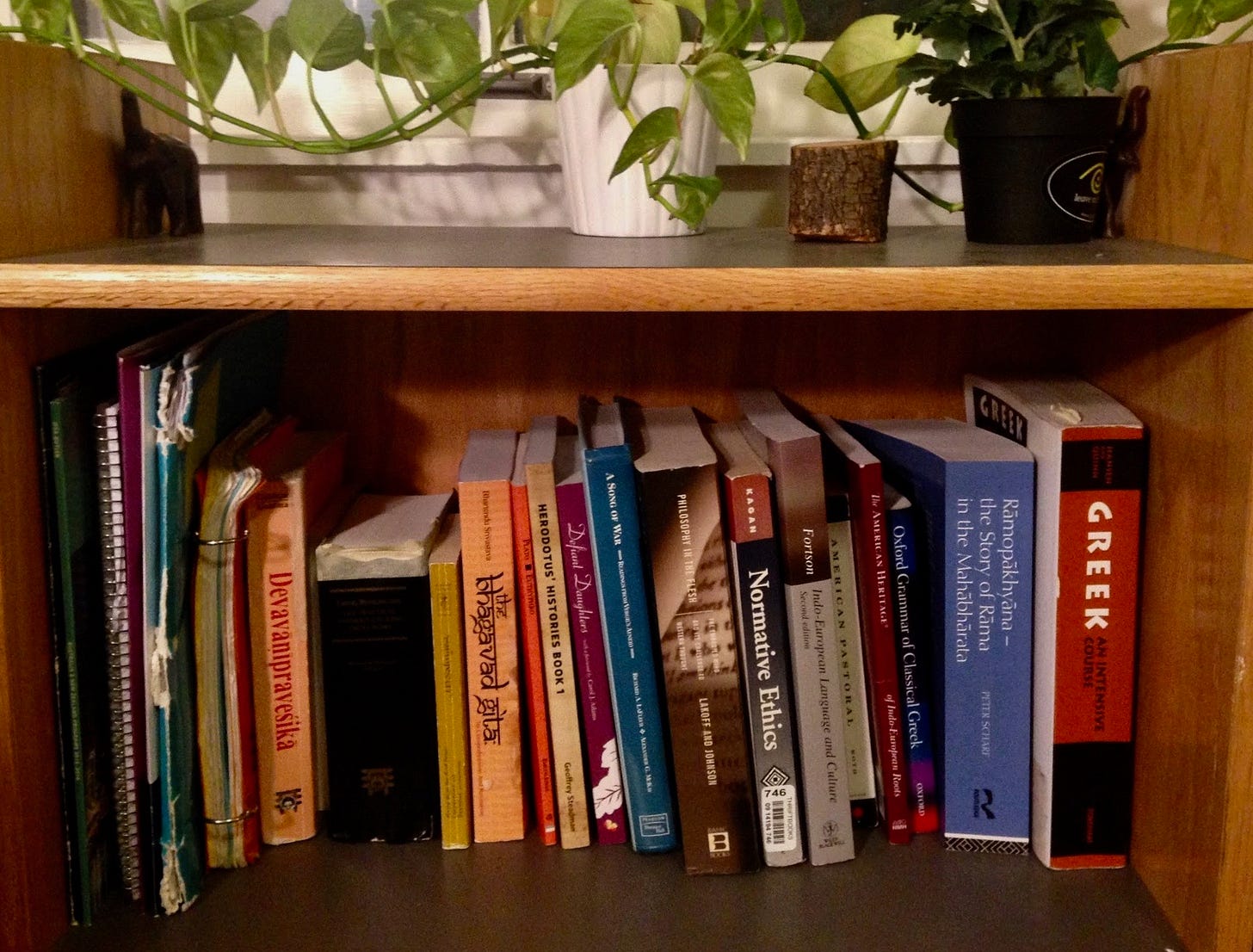

Since then, I’ve remained at the threshold of languages in our home. When my sister Vanita first started speaking a strange mix of Hinglish babble, I was the only person in the family who could understand her. I settled into English for most family and Hindi with my grandparents and Indian grocery store cashiers and salon ladies. I became enamored with Latin in middle school and Ancient Greek and Sanskrit in college. Most recently, I’ve been learning Spanish, running along the river to the rhymes of Karol G.

I took my first Latin class in seventh grade, after moving to a whiter, wealthier school district. Puzzling through sentences about Sextus who ex arborem cadit in Mr. Murray’s basement classroom was the closest I had ever come to time travel, and I fell in love. I started to learn Greek mythological family trees and celebrated Saturnalia; I read Juvenal over lunch and memorized the opening verses of the Aeneid.

My fascination with ancient Rome bemused my parents, and when I started to practice conversational Latin, they finally brought it up. “Are you ashamed?” they asked, pointing at the Hispanic kids back home who broke easily into Spanish. The irony plagued me with guilt. I felt staunchly Indian in many ways, spending summers in Lucknow and writing passionate history term papers against colonialism. But still, every New Year’s I could remember, I had resolved and failed to start speaking Hindi at home.

Instead of taking the plunge, I had always found lower-risk workarounds. I read Hindi with my mom, stumbling through animal fables at the same time as I recited Shakespeare in high school English. In college, with a PhD student I found on Craigslist, I started to study Sanskrit and successfully petitioned Princeton to reinstate it as a language program. As time passed, my parents let the language issue rest. Compared to most other desi kids, I was a cultural warrior, one immigrant child out of a dozen who hadn’t completely steamrolled her roots.

Despite winning many aunties’ admiration, I never overcame my guilt over my fear-fueled failures to speak more Hindi. I was afraid of making mistakes, botching genders for nouns that should demand ki instead of ka. I was afraid of facing linguistic technicalities, like which of the two forms of you to call my parents (the formal aap sounds obsequious; the informal tum sounds harsh). Most of all, though, I was afraid of having an American accent, like a laughably highbrow foreign Bollywood heroine. What I spoke felt less important than how.

I always knew that my parents sounded different than most American adults. As a kid, I once mocked Mamma for her accent on the phone, parroting her amin instead of I mean, buh instead of but. As she fell silent at the kitchen counter and said she couldn’t help it, I realized for the first time that I could hurt her. Papa wielded his accent with more defiance. “If I can understand them, they should be able to understand me,” he’d say, “and otherwise they can fuck off,” which seemed fair.

It took years for me to realize how amorphous my own accent is, too. I was walking to the train with a friend from Latin when my mom called.

“Wow,” she said when I clicked my phone shut, looking at me in amazement I will never forget. “You just sounded so Indian.” It felt more like a judgement than an observation. Sounding Indian was very different than sounding French or British, and anyone would rather be Hermione than Apu.

I grew more aware of my parents’ accents as people like my high school boyfriend pointed how they say involled instead of involved, cinnamum instead of cinnamon. I also became painfully conscious of my own reflexive accent mirroring. No American customer service representative can tell I’m Indian unless I spell my name; the Indians I met in Bombay were confused that I didn’t sound more American.

My accent mirroring is a subconscious empathetic gesture, a small reassurance to my interlocutors that I’m like them, that I hear them. When friends and family collide, though, the system breaks. I fumble into an uncomfortable compromise, garbling one sharp t after another soft one. I can’t choose a side, and everyone can hear it.

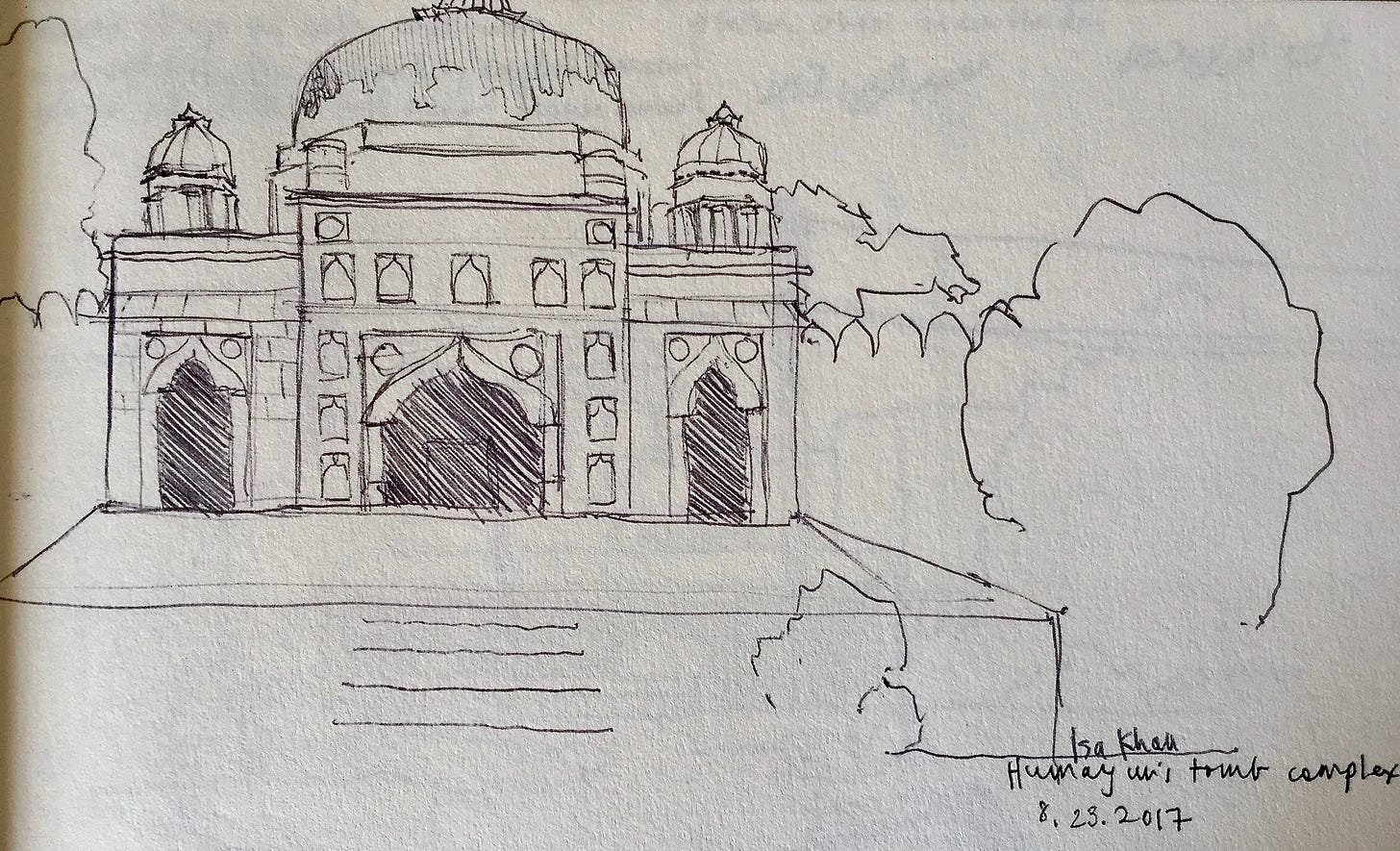

Moving to India changed everything about my relationship to name and language. Before I moved, I’d been going by Mishti, which felt easy and affectionate. In India, Mishti was not only awkward (my first swing partner was floored when I effectively told him to call me sweetie) but also superfluous. There, for the first time in my life, strangers could pronounce Vidushi properly. I stepped, dazed, into what felt like an entirely new name.

After years of insecurity, I was even more shocked to realize that my Hindi could pass. The driver of my first taxi in Mumbai, after a few minutes, told me, “I couldn’t tell from your Hindi that you aren’t from India — I thought you were just visiting from another city.” I stopped in surprise and remembered my repeated failed New Years’ resolutions. “Wow,” I said, in an accent suspended somewhere in between the Atlantic and the Arabian, in a voice note I labeled passing the test.

Most cab drivers, who were often migrants from Uttar Pradesh, actually recognized me as one of their own. We both used the Hindustani royal we, hum instead of mein, a Nawabi remnant in the now-poverty stricken state we’d left for new cities.

Over time, I’ve started to reclaim the delight of playing with my speech. Names, languages, and accents are powerful, but I realize that I can choose lightly between them and decide for myself what has meaning.

These days, I’m Vidushi to some, Mishti to others, Kiki to my sister who as a baby couldn’t say her d’s. I think less about my accent. I dabble without guilt in Hindi poems, Spanish songs, and the astonishingly beautiful Indo-European web they fit into. I still speak mostly English at home. But now, when I call Nanu on the phone, I don’t feel like I need to hide in my room.